A few notes about my approach to translating THE KURAL

For years it didn’t even occur to me to translate THE KURAL because the work is so venerated and so masterfully composed. It was only because of the gentle insistence of my Tamil teacher, the late Dr. K. V. Ramakoti, that I finally felt able to attempt doing so.

For those who may be interested in how I’ve approached this translation, here is a short excerpt from my preface to the book.

From “Cherishing Guests: A Translator’s Preface to Tiruvalluvar’s Tirukkural”

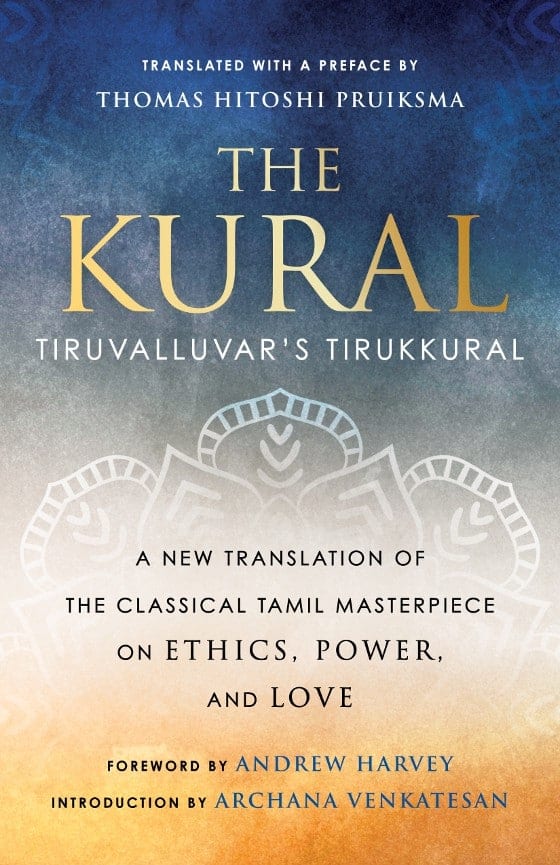

The Kural is by far the most translated book from Tamil literature, with over eighty translations into different world languages, some made directly and many more made by way of English, since English serves as a common language in both India and beyond. Many of these translations, however, are neither literary nor in print, and several are entirely unreadable. The best of them, that of P. S. Sundaram, captures Tiruvalluvar’s brevity and playfulness but does little to suggest his patterns of consonance and assonance. Here, for instance, is how Sundaram renders a verse from chapter 11, “Gratitude”:

103

Help given regardless of return

Is wider than the sea

Tiruvalluvar, The Kural, trans. P. S. Sundaram (New York: Penguin Books, 1991).

And here is a transliteration of this verse, with several elements of its patterns in bold:

103

payan tūkkār seyta utavi nayan tūkkin

nanmai katalir peritu

Very little of these patterns has made it into Sundaram’s translation. My experience, however, suggests that more is possible. Even if one can’t achieve exactly the same effect with the same means—the same exact sounds in the same exact order—one can try to achieve a similar effect with similar means. That, in any case, is what I’ve tried to do, while also trying to honor root meanings. In this verse, for instance, tūkkār means literally “those not weighing”:

103

The weight of good done without weighing results—grace

Greater than oceans

Two other aspects of Tiruvalluvar’s poetry have eluded previous translations: the dissimilar lengths of the lines in a kural and the absence of punctuation. (Tamil didn’t have or need punctuation as we know it until the language encountered English.) Accordingly, I’ve tried to honor this dissymmetry in each verse and have also drawn on the example of the North American poet W. S. Merwin, who relinquished punctuation while writing his fifth book, The Moving Target. He felt, and I feel, that punctuation staples a poem to a page, pinning it within the rational protocol of written language and literal-minded prose. I want instead to evoke the oral and aural qualities of Tiruvalluvar’s intelligence, which cannot be fully captured by mere rationality. He speaks to all of our senses with all of his. So although at times I use a dash to make the meaning clearer, as well as initial capitals to suggest the formality of the verse, I have strenuously avoided any other kind of punctuation. This is meant to encourage readers to read the poems out loud and to allow their breath and their ears to participate in the discovery of the verses’ many patterns and meanings. In some cases the dashes are also meant to suggest a form of expression in Tamil that doesn’t have an exact equivalent in English.

Many of Tiruvalluvar’s statements equate one thing to another, as we might do in English with a form of the verb “to be.” I might say, for instance, “My name is Thomas,” and we’d understand that the verb “is” equates “my name” and “Thomas.” In Tamil, however, one doesn’t need a verb to make such a statement. One can simply place the two elements beside each other and their connection will be clearly understood. What looks literally like “My name Thomas” means in fact “My name is Thomas.” But in English, if we write “My name Thomas,” we’re not really writing in English. Unless, that is, we say the statement out loud and add a pause of some significance between “name” and the name itself: “My name—Thomas.” Now we have something that brings the two forms of expression a bit closer. And notice that this not only returns us to language as it’s spoken but to the drama that such a pause out loud can convey.

I have thus used dashes to indicate places where a pause may help to bring the poem off the page. Here’s an example from chapter 2, “The Glory of Rain”:

15

That which ruins and raises up

The ruined—rain

One could, of course, translate the dash here as “is,” but I feel that it’s closer to the spirit and energy of the original to convey that meaning with a more meaningful silence. Doing so also keeps the poem more open to possibility and to different interpretations, as all good poems tend to do. Throughout this translation, if a verse does not seem at first to make sense to you, speak it out loud and you may find it revealing its patterns of meaning to your ear. Poetry begins in the ear of the heart, which we can learn to hear through the ear of our body.

You can read a longer excerpt from the preface on the award-winning blog of Beacon Press, Beacon Broadside: How I Embarked on a Literary Translation of The Kural, the Classical Tamil Masterpiece

One Last Note

No translation, especially of a work as extraordinary as this one, can ever hope to be definitive. With the guidance of many wise friends, I’ve taken this translation as far as I can and am unable to enter into debate about specific verses or choices. If what I’ve done helps to stimulate discussion in English, that alone is cause for celebration.